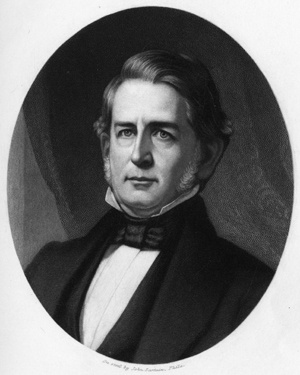

Joseph Charless, 1772–1834

|

Born in County Westmeath, Ireland, on 16 July 1772, Joseph Charles was the only son of Edward and Ann (Chapman) Charles. As a young man, Joseph participated in an Irish uprising in 1795 and fled to France. A year later, he took sail for America, landing in New York. Upon arriving in America, he added an extra “s” to the end of his name so Americans would pronounce it as it was in Ireland, with two syllables and not one. A printer by trade, he joined a publisher named Matthew Carey, who had the largest publishing business in Philadelphia, and with the help of his new employer, he met many of the movers and shakers of the time. Joseph married Sarah (Jourdan) McCloud, a widow with a young son, in Philadelphia in 1798. Together, they would go on to have more children: Edward, John (who died as a teenager), Joseph Jr., Elizabeth Ann “Eliza,” Ann, Chapman, and Sarah. Like many young men, he saw great opportunities in the new country, moving in 1800 to Lexington, Kentucky, where he began printing the first of several newspapers, the Independent Gazetteer, and then, after settling in Louisville, the Louisville Gazette. Although the Louisiana Territory had a substantial population by the early 1800s, there was no printing press. That meant that if anything had to be printed, it had to be sent to the nearest press in Kentucky. In 1808, Meriwether Lewis, the territorial governor, offered Joseph a contract to publish government documents in St. Louis, which he accepted. In July 1808, Charless published the Missouri Gazette, the territory’s first bilingual (French/English) newspaper. He then went on to print the first book west of the Mississippi, The Laws of the Territory of Louisiana, and, a few years later, the first almanac in the west. For almost a decade, he was the only printer in the Louisiana Territory. |

Joseph Charless Photo from Thomas J. Scharf, History of St. Louis City and County, volume 2, 1883, public domain |

|

Charless was a man of opinions, not all of which were popular. He was not afraid to take on the wealthy and influential when he thought they were at fault, and he believed in limiting the spread of slavery. He often came under verbal and occasional physical attack for standing his ground. In 1820, he retired, selling his newspaper to a man who renamed it the Missouri Republican. Two years later, Edward Charless bought his father’s paper back and it remained in publication until the end of World War I. Joseph Charless’s “retirement” kept him busy. He held a variety of jobs, such as pharmacist, real estate agent, and boardinghouse manager in the fourteen years he had left to him. He established a reading room next to his newspaper’s offices and a public library. After his death on 28 July 1834, he was interred at Bellefontaine Cemetery. During his lifetime, Joseph Charless brought the printed word to the American frontier. He made it possible for news and culture to reach the farthest edges of the new country and for education and public debate to flourish as the country continued to grow. Written by Ilene Murray © 2024, St. Louis Genealogical Society |

|

Return to St. Louis City/County Biographies.

Last Modified: 26-Aug-2024 16:22